Buddhist Meditation Practice for the Boston Marathon Tragedy

This Monday I woke up and did what I’ve done every morning for the past 3 weeks: I practiced a compassion meditation in honor of my recently deceased father. He had been sick for many years before he passed and, as odd as it may sound, had a better death than I had imagined was possible. It was transformational for me to hold his hand, look him in the eyes and speak words of comfort to him as he ceased to breathe. While I have missed him every day in these last three weeks, I took comfort in his peaceful departure.

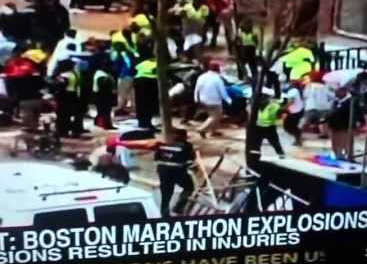

A few hours after my morning practice I saw my first photo from the Boston Marathon tragedy. There was nothing peaceful about this experience. Smoke. Disarray. Confusion. More photos surfaced. Blood. Pain. Death. I thought of my former home in Boston, my Buddhist teacher Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche crossing that finish line just a few years ago. The potential ramifications of such an event. And my heart broke.

At the time of this writing at least three are reported dead and more than 100 injured. The dust is still settling and the “who” and “why” may not be forthcoming for quite some time. As someone who has spent the last year in grief over the loss of one loved one or another, I’d like to posit that dwelling on “who” and “why” may not be the most helpful thing to do in this particular moment. Perhaps the most helpful thing to do is to allow yourself to feel your heart.

The compassion practice I am doing in the midst of this tragedy is known as tonglen. Tonglen is a Tibetan word which can be translated as “sending and receiving.” It is a practice where you breathe in the things that are painful or uncomfortable for others and breathe out, sending those people pleasing, soothing qualities. It is a practice that enables us to be open, vulnerable and yet offers strength within that context. I offer pith instructions below (click here for more from Shambhala acharya Pema Chodron).

1. Gap

To begin, sit in meditation for at least 10 minutes. For instructions on how to meditate, click here. When you are done, raise your gaze a bit and allow yourself to experience a brief mental gap. Allow your mind to experience its own vastness. Connect to the present moment, without an object of meditation.

2. Textures

As you return to focusing on your breath, begin to place your mind on a variety of textures. As you breathe in, imagine that you are breathing in hot, heavy energy. This may feel a bit claustrophobic, which is fine. Breathe in this weightiness, through every pore of your body. Then when you exhale, breathe out fresh, cool energy. Do this practice of breathing in and out, visualizing these textures, for a few minutes.

3. Individuals

Having gotten the hang of the ebb and flow of connecting your breath to these textures, bring to mind an individual involved in this tragedy. It might be someone you know of, or perhaps you have only seen their photo. Try your hardest not to shut down your heart but remain open to the scenario. As you breathe in, feel as if you are breathing in their specific pain. You may breathe in fear, or physical discomfort, or grief. We may not know exactly what everyone in Boston is going through but we all know those basic experiences. You can breathe that feeling in, and breathe out a sense of calm, or relief, or spaciousness to those people. Whatever comfort you can offer in this moment, offer it on the out-breath.

4. Go Bigger

As you conclude working with a specific person or persons during your tonglen practice, you can extend your practice larger than that scenario. For example, you can extend that aspiration of relief to everyone else who lives in Boston and is grieving or in physical pain. The idea is to make this practice radiate far and wide, so all beings feel a sense of comfort as a result.

It is important to start as personal as possible in this practice, before going big. If you sit down and just contemplate how many people are in pain and attempt tonglen for them you may end up having this be a theoretical exercise. If you start with one person, even if you have only seen their picture, you have a greater chance of it becoming real and experiential. At the end of your tonglen practice, return to the basic meditation practice for another few minutes. Ground yourself back in the present moment by focusing on the natural flow of your breath, sans visualization.

Through engaging this practice we learn to become open-hearted, without judgment. We can offer our empathetic aspirations for everyone affected by this tragedy, without placing blame. This is, of course, not to excuse or downplay the role people have played in creating this horrific event, but before we leap to conclusions perhaps we can first just offer our hearts and sympathy.

In the days and weeks to come we may be able to offer more than our sympathy, prayers and practice. I look forward to contributing in other ways to the relief efforts. Yet when something like this happens, we often say, “There are no words.” Perhaps we should not yet go to words. For those of us located outside of the Boston area we may not yet be able to go to deeds either. For now, maybe it is OK to go to our vast broken heart.

By Lodro Rinzler

Over the last decade Lodro Rinzler has taught numerous workshops at meditation centers and college campuses throughout the United States. Lodro’s book, The Buddha Walks into a Bar: A Guide to Life for a New Generation (Shambhala Publications, 2012) explores the intersection of Buddhist philosophy and modern day living. His column, What Would Sid Do, appears regularly on the Huffington Post and his writing has appeared in Shape Magazine, Real Simple Magazine, the Shambhala Sun, Buddhadharma, Reality Sandwich, and the Good Men Project.